Through the Lens of Asset-Based Community Development and Results-Based Accountability™

Dan Duncan, Senior Consultant

Results Leadership Group

Faculty Member, Asset-Based Community Development Institute.

As more collective impact initiatives are launched around the world, many participants are realizing that effective collective impact will not simply occur through better coordination of services, whether this is done by one organization or even a multitude of organizations. It requires a “sea change” in our thinking, and the development of community-led strategies focused on achieving real change in the lives and communities we serve.

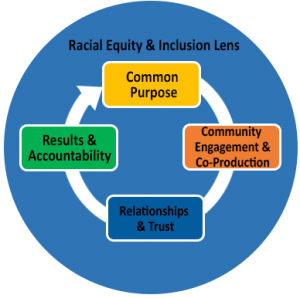

Also, when we talk about collective impact and community- led strategies we must be clear that the foundation of effective collective impact must be based on a racial equity and inclusion lens to make sure no one is left behind. Applying a racial equity lens is not a separate principle of collective impact, nor it is a separate program, to be applied when needed. It is the foundation to which all activities should be based.

“Equity is just and fair inclusion into a society in which all can participate, prosper, and reach their full potential.” PolicyLink

Therefore, to apply a racial equity & inclusion lens data must be disaggregated by race, gender, age, class, location, etc. to enable us to truly develop the range of strategies necessary to ensure that race does not predict one’s success while also improving outcomes for all. To accomplish this, we need to target strategies to assist those most affected. We also must move beyond “services” and focus on changing polices and institutions. Government Alliance on Race & Equity.

Finally, the only way to truly understand the story behind the data is to engage with community members about their lived experiences.

Based on my experience as a faculty member of the Asset-Based Community Development Institute at Northwestern University and as a long-time United Way professional and consultant, I believe that the framework of action for effective collective impact incorporates the following four components, which rest on a foundation of equity and inclusion:

- A clear, common purpose;

- Community engagement and co-production;

- Relationships and trust; and

- Results and accountability.

In this paper, I will discuss these four components in detail.

A Clear, Common Purpose

Effective Collective Impact Starts with a Clear, Common Purpose

The first component of effective collective impact is a Clear, Common Purpose. According to John Kania & Mark Kramer, in their 2011 article in the Stanford Social Innovation Review,

“Collective Impact requires all participants to have a shared vision for change, one that includes a community understanding of the problem and a joint approach to solving it through agreed upon actions.”

This shared vision for change – a common purpose – must go beyond the interests or needs of individual participants, who may try to prioritize incremental goals like providing better services or raising more funds. The common purpose serves as the “north star” of a collective impact effort, and it should relate to the hopes and aspirations of the people whom the effort seeks to serve. We cannot develop a true common purpose without engaging the people we serve in the discussion and ultimate adoption of that purpose. Therefore, one of the primary roles of a backbone organization is to ensure that there is an initiative-wide agreement on the common purpose and that we have engaged all of the required participants in the planning and implementation, including the people we seek to serve.

Setting a Clear and Common Purpose

The Results- Based Accountability™ (RBA) framework, developed by author and director of the Fiscal Policy Studies Institute, Mark Friedman, can help identify a common community agenda and, at the same time, build a culture of measurement and shared accountability (the fourth component in my list).

The first two questions of RBA’s “Population Accountability Questions” can provide a useful framework to help a collective impact effort develop a clear, common purpose.

The first two questions are:

The RBA Framework – 7 Population Accountability Questions.

- What are the quality of life conditions we want for the children, adults and families in our community?

- What would these conditions look like if we could see them?

- How can we measure these conditions?

- How are we doing on the most important of these measures?

- Who are the partners that have a role to play in doing better?

- What do we propose to do?

1. What are the quality of life conditions we want for the children, adults, and families in our community? The answers should be stated in plain language that everyone can Not in the language of bureaucracies and professionals. Quality of life conditions are things like “communities are safe” or “children succeed in school, life or work.”

2. What would these conditions look like if we could see them? This is a forward-looking vision of what we are trying to achieve. It should be clear that we are working to improve community conditions and the lives of the people that call the community home — not just a better service system. For example, a low crime rate might help us visualize a safe community. A stellar high school graduation rate might help us visualize a community in which children are succeeding in school.

Through the use of these two questions, collective impact efforts are more likely to land on a common purpose that is understood by all participants and, more importantly, are more likely to be engaging and inspiring to everyone involved, including the people served by the effort.

Furthermore, combining the RBA approach with the principles and practices of Asset-Based Community Development (see the next component for a discussion of ABCD) can help members of a collective impact effort recognize and value that the people they serve are experts in their own lives. They bring gifts in the form of unique skills, knowledge, and abilities to the table. As members of a collective impact effort, we must be cognizant and inclusive of others’ lived experiences. We must work with the people we serve to identify the intersections of our work with their hopes and dreams. Understanding these intersections is crucial to collectively determining a clear, common purpose for a collective impact effort.

One note of caution: Based on my experience as a faculty member of the Asset-Based Community Development Institute, engaging the community in this process and dialogue is more than just adding a few community members to the existing collective impact “table.” This method of engaging the community tends to create an unequal power dynamic. The “community representatives” brought to the table are often viewed by professional participants as being less powerful or knowledgeable. The community representatives also often perceive this power imbalance and have trouble understanding the professionals who frequently speak in the language of acronyms and jargon.

Additionally, it is faulty thinking to expect the few “community representatives” we often invite to the table to represent the entire community from which they come. For instance, no one has ever asked me to represent all of the white males in my community, but I have seen others expect a single community representative to represent all of the Hispanic females in her neighborhood. Very little true dialog and understanding can occur with this approach. To be effective, we must create space for residents to come together themselves to discuss their hopes and dreams and answer the two RBA questions. We, as the professionals, need to “lead by stepping back” to create this safe, caring space. We can then use the community’s feedback and answers to the two questions as the foundation for a clear, common purpose embraced by all.

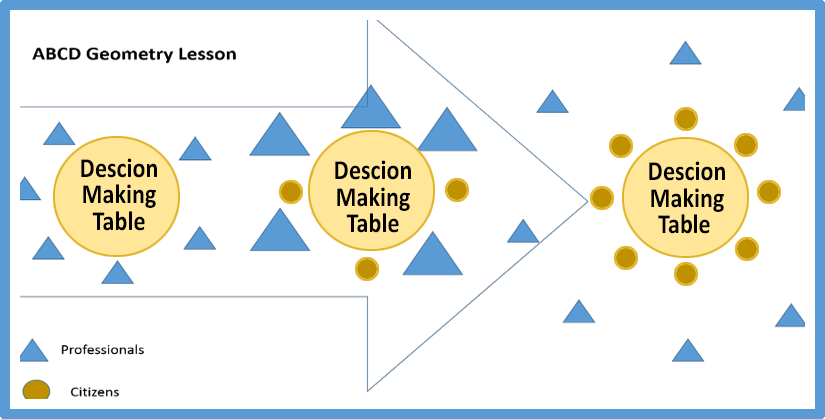

The Asset-Based Community Development Geometry lesson helps illustrate this poin

In the ABCD Geometry lesson, “triangles” represent professionals and “circles” represent citizens. The goal is to move from only triangles (or professionals) around the decision-making table to tables of circles (or citizens). For true community engagement, professionals need to step back to create space for citizens to discuss their own hopes and dreams and the roles they can play to achieve their dreams. True support is when professionals allow citizens to be in charge of their own destinies and then step in when their help is requested. According to one of my ABCD colleagues, “Professionals need to be on tap not on top”.

Community Engagement and Co-Production

During my years with various United Ways, I launched a number of collective impact initiatives. One thing they all had in common was a focus on community engagement that employed the principles of Asset-Based Community Development (ABCD).

ABCD is a place-based framework pioneered by John McKnight and Jody Kretzmann, founders of the ABCD Institute at Northwestern University. ABCD builds on the gifts (skills, experiences, knowledge, and passions) of local residents, the power of local associations, and the supportive functions of local institutions to build more sustainable communities for the future.

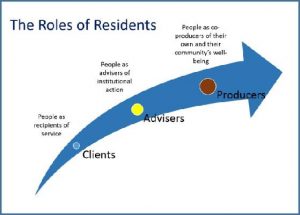

In my work, I have found that one of the most powerful components of collective impact success, as well as the most misunderstood, is community engagement. We often believe that community engagement is the process of engaging the people we serve as advisors to help improve our programs and services. For example, if an individual has particular knowledge about her neighborhood and its residents, she may advise an agency about ways to most effectively serve the neighborhood and define what services the neighborhood actually wants and/or needs.

However, community engagement frequently stops here. Professionals often believe that we have achieved community engagement when we ask people, “What do you need and how would you like it delivered?” Then we change our service model based on the input received. However, I believe we have the opportunity to make an even greater difference in our communities when we help the people we serve to move beyond their roles as clients and advisers to become producers of their own community’s well-being.

We have a much better chance of achieving the results we are striving for when we create the opportunity for people to share their gifts and serve as co-producers.

My experience tells me that if we truly want to make a difference, we need the people we serve to act as co-producers. We cannot do it without them.

In the most successful and effective collective impact initiatives, the people we serve have the opportunity to participate as clients, advisors, and/or co- producers, depending on what is appropriate in the context. For example, there are times when people need to be a client. If a person breaks his leg or has a disease, he rightfully needs to be a client or patient. In this case, the individual is dependent on the services of a professional. Agencies and funders also need the advice and input of the people they serve, in order to offer people what they truly need.

In addition to asking people “What they need?” we need to ask “What can you contribute?” And “How can we help you share your gifts?” As co-producers, community members become part of the solution. For example, imagine that as part of an early education collective impact initiative we want to make sure that every household in a neighborhood with young children has age-appropriate books to help them learn to read. Rather than funding an agency to buy and distribute books, we could find a group of neighborhood parents who have a passion for reading; these parents could organize the book drive. This activity does not require institutional or government resources. This is an example of something residents can do themselves if they are engaged as part of the solution. Treating community members as producers of their own well-being, rather than merely recipients of social services, is important because we need their assistance to achieve lasting impact. For, example, according to the County Health Rankings, healthy behaviors and social and economic factors are much more important than clinical care in influencing the health of a county and its residents. The role of people as co-producers is critical to creating healthy community.

When we adopt this approach as part of a collective impact effort, agencies and professionals can play a powerful role in removing barriers. By playing this role, we can ensure that all community members have an opportunity to share their skills and experiences and do whatever they can to improve their lives and their community. We need everyone’s gifts to create the change we all desire for families, children, and ultimately the community. For me, the foundation for effective collective impact is genuine community engagement and co-production.

Relationships and Trust

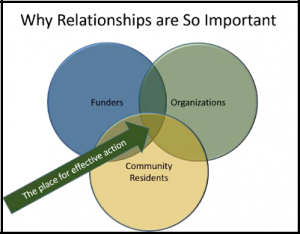

The third component of effective collective impact is Relationships and Trust. To achieve the results, we are striving for, it takes funders, organizations, and the people we serve to all work together. It’s the intersection of the collective actions of funders, participating organizations, and the people we serve that is the locus for true effective collective impact.

This graphic illustrates why relationships and trust building are so important to effective collective impact.

Strong collaborations are based on the trust that comes from building authentic relationships. These relationships cannot be legislated or mandated from the top. To build relationships, we must be clear that organizations do not collaborate; people collaborate, based on common purpose and trust. Therefore, one of the primary roles of a backbone organization is to ensure that there is an initiative-wide agreement on the common purpose of the effort. Additionally, a backbone organization must provide opportunities for the participating organizations’ staff and volunteers to interact at every level. To build relationships and trust these opportunities must include person-to- person interactions. You cannot just build the relationships and trust required via email and the internet.

For some, taking time to build relationships and trust might seem superfluous. However, it is a critical component of collective impact. Opportunities for relationship building should be incorporated into all meetings and reinforced as an important “fundable” activity. It is only through time that relationship and trust can be developed.

Relationships Among Organizational Partners

Relationship building is not just the work of the early formation phase of a new collective impact initiative. It is something that needs to be integrated and supported throughout the entire process to ensure organizations maintain trust, even through periods of turnover.

Organizations may have a long history of working together and collaborating, but when key players leave, the partnership has the potential of re-setting to zero. For example, imagine that one of your staff members reports that a partner that has been providing your nonprofit’s clients with priority access to their parent education classes has decided to no longer provide that access.

When key people change, assume the partnership re-sets to zero. Therefore, we must always be focused on building relationships and trust.

You call your counterpart at the nonprofit and discover that the person you had the relationship and partnership with has left the nonprofit; the new person did not see the value in continuing the arrangement.

To avoid a situation like this, we need to always focus on relationship building and not just assume that organizations will always work together at the level needed.

Relationships Between Funders and the Organizations They Fund

As a long-time funder with United Way, I learned that to be truly effective, we needed to change our relationship with the nonprofits we funded from a “top-down” Grantor-Grantee model to a partnership model, with both sides bringing value to the table. By working together as partners and building the relationships and trust necessary to truly be effective, our funding decisions transformed from merely meeting nonprofit needs to achieving real, measurable impact in the communities we all served. By making this shift, the nonprofits we funded became true partners around the table.

Relationships with the People We Serve

Finally, engaging the people we serve in a collective impact initiative as co-producers is critical to the success of the effort. We cannot do it without them. To engage the people being served as co -producers, we need to build the same level of relationships and trust with them. We must treat the people we serve as experts in their own life with gifts to bring to the table for their own and their community’s well-being. As part of this effort, we must work with the people we serve to identify the intersections of our work with their hopes and dreams. Understanding these intersections can help us collectively determine how we can work together to achieve those dreams. Based on my experiences one of the best ways to build relationships and trust with the people we serve is through in-person “learning conversations”. In learning conversations we start by asking questions rather than by just giving answers to the issues as we perceive them.

Taking the time to build relationships and trust at all levels is a critical component of effective collective action and impact. For example, in my personal experience, it is much easier for agency partners to move from a competition model to one of collaboration and partnerships if there are strong relationships and trust between the leaders and key staff.

“Organizations do not collaborate, people do based on common purpose, relationships and trust.”

One of my principles is “Organizations do not collaborate, people do based on common purpose, relationships, and trust”.

Results and Accountability

The fourth component of effective collective impact is Results and Accountability. The participants in a collective impact effort must be willing to be held accountable for improving the lives and the communities they serve. To accomplish this, it is critical to have two things in place: 1) A culture that facilitates learning and adapting in a complex world; and 2) Processes to collect and share the information necessary to track outcomes and results.

A Learning Orientation

Collective impact efforts – whether they be a project, initiative or organization – must embrace a learning orientation. They must be willing to collect information relative to their effectiveness. They must be willing to continuously improve, share, and learn based on what is working and, more importantly, what is not working. For many nonprofit organizations, the fear of losing funding has precluded a robust discussion about what is not working. More than once I have heard the comment “If we admit our strategy may not be working to our funder, they may pull our funding.” Therefore, for effective collective impact, it is critical that funders create a safe place to discuss what is working, as well as what is not. Public agencies must be willing to enter that space and learn.

In the for-profit world, many of our most advanced scientific developments have resulted from the willingness to innovate and take risks, without the fear of failure. Others have resulted purely out of mistake. Post-it Notes, the microwave oven, and Penicillin are examples

of learning from our mistakes. We need to embrace this level of innovation and risk-taking in the nonprofit sector as well.

The Complex World of Collective Impact

In Getting to Maybe: How the World is Changed, authors Frances Westley, Brenda Zimmerman, and Michael Patton highlight that there are three types of problems: simple, complicated, and complex. Simple problems are like baking a cake. A few steps and ingredients are all it takes to get a delicious cake. Complicated problems are like flying a rocket to the moon. Getting to the moon requires a longer recipe with more steps and ingredients. With complicated problems, all of the ingredients always respond the same; if you follow the recipe, you will always get to the moon. Complex problems are like raising children. As parents, if you try to raise your children exactly the same, they all turn out totally different.

Collective impact operates in a complex world. Because we are dealing with human beings, the variables are always changing. What works for one person may not work for another, and what worked yesterday may not work today. Therefore, logic models designed to address complicated problems will not work for complex programs. Instead, we need data and information so we can make the necessary mid-course corrections. Without outcomes data, we do not have the information we need to make the changes needed to achieve our outcomes and results.

Results-Based Accountability

Over my nonprofit career as a United Way professional, I have found Results-Based Accountability™ to be an effective framework for collecting and sharing the data needed to learn and improve.

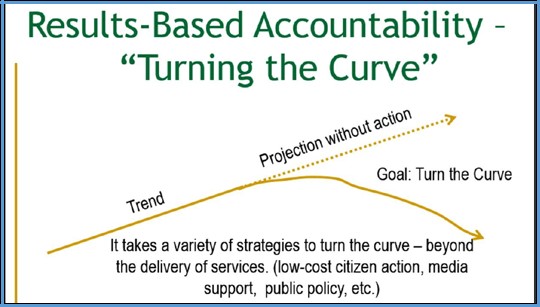

RBA is an ends-to-means approach. First, we identify the quality-of-life conditions (population results) we want for our children, families, adults, and communities. Then, we assign corresponding measures (indicators) that help us track whether we are achieving these quality of life conditions. Once we develop the appropriate strategies needed to “turn the curve” on our indicators, we establish performance measures to track and improve the performance of our individual programs and strategies.

Turning the Curve

RBA introduces the concept of “turning the curve,” or accelerating a positive data trend/ reversing a negative one. Rather than focusing on rapidly achieving targets or goals, RBA emphasizes improvement of quality-of-life indicators over time. Shifting to turn the curve thinking can help foster long-term action, and it also helps highlight incremental success.

More importantly, a focus on overarching community results and “turning the curve” recognizes that creating measurable, community-level change requires a variety of strategies beyond the delivery of services. Strategies must include community engagement and co-production, public policy changes, media engagement, and service enhancement to create sustainable long- term change.

It takes a variety of strategies to ‘turn the curve’.

The concept of turning the curve makes it very clear that for a collective impact effort to be successful, we have to engage many partners and implement a number of strategies. No one institution or program can turn the curve alone.

Performance Measures

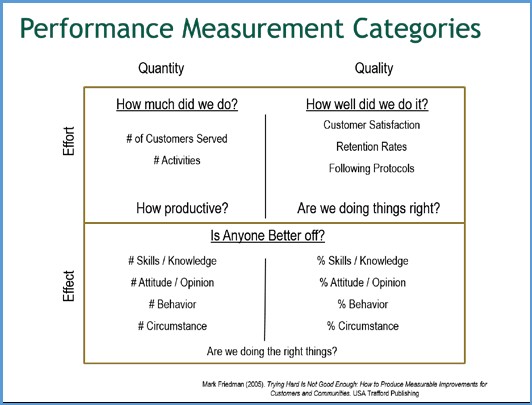

The RBA framework provides a collective impact effort the ability to develop effective community-based strategies and enhance service-delivery activities through the adoption of performance measures. Performance measures answer these three questions:

- How much did we do?

- How well did we do it?

- Is anyone better off?

The answers to these three questions provide the collective impact leadership and the individual service providers the information they need to identify how productive they are (e.g. number of people served, units of service delivered, etc.), the quality of their service delivery (e.g. retention rates – do the clients stay in the program long enough to receive the benefits?), and most importantly, the effect of their service delivery –are they doing the right things to truly make a difference in their community and for the people they serve. Common measures of program effectiveness often describe the % of program participants with changed knowledge, attitudes, behaviors, and/ or circumstances.

In addition, I have found the Performance Measurement Categories graphic a great tool to use to help the collective impact participants identify and collect the data they need to truly make a difference:

More importantly, a focus on overarching community results and “turning the curve” recognizes that creating measurable, community-level change requires a variety of strategies beyond the delivery of services. Strategies must include community engagement and co-production, public policy changes, media engagement, and service enhancement to create sustainable long- term change. RBA provides a simple, understandable framework to develop and communicate a common agenda and the shared measurement system necessary to drive collective action.

Summary

As you develop or enhance your collective impact effort(s), focusing on the four components that I have laid out in this paper (a clear, common purpose; relationships and trust; community engagement and co-production; and results and accountability) built on the foundation of racial equity and inclusion will help provide the framework you need to effectively achieve the five conditions of collective impact, and more importantly, improve lives in the communities you serve.

References:

Kania, John & Kramer, Mark. Collective Impact. Stanford Social Innovation Review. Winter, 2011.

PolicyLink, http://www.policylink.org

Government Alliance on Race and Equity, http://www.racialequityalliance.org

Westley, Frances, Zimmerman, Brenda, and Paton, Michael, Getting to Maybe: How the World is Changed. 2006.

Friedman, Mark. Trying Hard is Not Good Enough: How to Produce Measurable Improvements for Customers and Communities. 2005.

County Health Rankings, http://www.countyhealthrankings.org

Asset-Based Community Development Institute, http://www.abcdinstitute.org

Dan Duncan

Senior Consultant

Results Leadership Group, LLC

“The Nation’s Leading Results-Based Accountability™ Resource”

11300 Rockville Pike, Suite 1001

Rockville, MD 20852

Mobile: 512-788-8646

Fax: 301-907-7545

Dan Duncan has extensive professional management experience in the nonprofit and for-profit professional service sectors. He has used this experience to provide training and consultation both nationally and internationally to help communities, nonprofits, and governmental organizations enhance their community work through the use of the principles of Results-Based Accountability™, Asset-Based Community Development, and Collective Impact. He is also a faculty member of the Asset-Based Community Development Institute at Northwestern University.