The Development of a Tailored Support Needs Assessment Tool for UnitingCare Disability’s Flexible Options Program:

Life Visioning and Support Needs Assessment Tool

Prepared for UnitingCare Disability by Pathways to Leadership and Rachel Dickson Consulting

May 2013

Purpose and Introduction

Pathways to Leadership and Rachel Dickson Consulting were approached by UnitingCare Disability’s Flexible Options program in April 2013 to develop a tailored support needs assessment tool. It was outlined that the primary function of the tool would be to identify the hours of support needed per week for each individual supported under the ILSI initiative. Accordingly, the allocation of hours would be in line with the Australian Government’s Family and Community Service division’s model of Drop In Support funding. UnitingCare Disability have found that standardised assessments of support needs are time consuming, with complex questions that don’t allow for flexibility. The main objectives of this project are to develop a support needs assessment tool that is:

- user friendly,

- flexible,

- identifies the number of hours of support each individual requires per week, to fit in with FACS Drop In Support bands, and

- links in with the person centred planning process.

The initial step in the tool development is to review the literature on the construct of support needs and how these are measured. A review of both standardised and non- standardised measures of support needs will follow, concluding with recommendations for the development of an in house assessment tool for UnitingCare Disability.

Conceptualising Supports

Defining Supports

Supports are needed and used by everyone. Supports may be defined as resources and strategies that promote the development, education, interests and well-being of a person to enhance independence and productivity, community integration and/or improved quality of life (Luckasson et al, 2002; Thompson et al., 2004).

It is widely recognised that relevant and effective supports can improve everyday life functioning and further empower people with disability to live the life they choose (Riches, Parmenter, Llewellyn, Hindmarsh & Chan, 2008). A system of supports model is now advocated by the American Association on Intellectual and Developmental Disability (AAIDD).

A Supports Model

In the past, disability was understood by the medical model as a characteristic of the individual that required medical treatment or intervention to resolve the problem.

More recently, deficit based approaches have been criticised for excluding individuals from participation in activities due to the existence of these deficits (Kirby et al., 2004). In contrast, contemporary approaches to understanding disability consider the construct to be an interaction between the characteristics of the individual and the context in which they live, called a bio-psycho-social model. It is this model that underlies the World Health Organisation’s (WHO) International Classification of Functioning, Disability and Health (ICF; WHO, 2001).

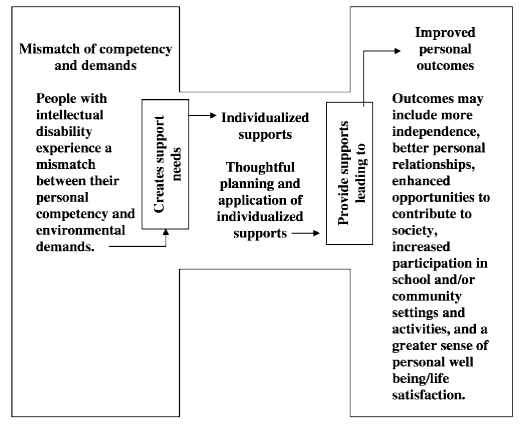

This dynamic interaction between the person and their environment also underlies the AAIDD classification model (Luckasson et al., 2002). This model, called a Supports Model, involves the application of specific supports to reduce limitations experienced by the individual and to facilitate achievement of desired personal outcomes. Fundamental to this model, and to the WHO model, is the view that the state of disability is not fixed but rather, constantly changing as a function of the individual’s limitations and available supports. Reducing the experience of disability results from the provision of interventions, services and/or supports (Luckasson et al., 2002). Human functioning is enhanced when the person–environmental mismatch is reduced and personal outcomes are improved.

Figure 1. Supports model (Thompson, Bradley, Buntinx et al., 2009

The Support Model (AAIDD) categorises the intensity of support required into four levels:

- Intermittent: Supports on an ”as needed basis,” characterised by their episodic (person not always needing the support[s]) or short-term nature (supports needed during life – span transitions, e.g., job loss or acute medical crisis). Intermittent supports may be high or low intensity when provided.

- Limited: An intensity of supports characterised by consistency over time, time- limited but not of an intermittent nature, may require fewer staff members and less cost than more intense levels of support (e.g., time-limited employment training or transitional supports during the school-to-adult period).

- Extensive: Supports characterised by regular involvement (e.g., daily) in at least some environments (e.g., school, work, or home) and not time-limited nature (e.g., long-term support and long-term home living support).

- Pervasive: Supports characterised by their constancy, high intensity, provision across environments, potentially life-sustaining nature. Pervasive supports typically involve more staff members and intrusiveness than do extensive or time-limited supports. (Luckasson et al., 2002, p. 152).

The intensity of support needs will fluctuate over time, settings, situations.

While the aim of a supports system is the provision of adequate and relevant natural and paid supports, to assist people with all types and levels of disability to more actively participate in their communities and live more satisfying and fulfilling lives, a significant challenge is the actual identification and assessment of support needs (Riches et al., 2008). The planning of supports must start with the individual’s needs and wants (Riches et al., 2008).

Frameworks for Deconstructing Need

World Health Organisation’s International Classification of Functioning, Health and Disability (WHO-ICF, 2001)

As previously mentioned, the bio-psycho-social model of conceptualising disability is at the core of the ICF framework, wherein the individual’s state of functioning is considered to be a dynamic interaction between:

- The Individual (including their health condition or impairment),

- The activities they wish to participate in, and

- Contextual factors that may either restrict or facilitate participation (including environmental and personal factors).

(WHO, ICF 2001)

These three components of a person’s functioning are further divided into multiple domains.

The first component, The Individual, is considered in terms of Body Functions (e.g.,mental, sensory, voice and speech, cardiovascular etc.) and Body Structures (e.g., structures related to movement, speech, nervous system etc.).

Second, the Activities and Participation domains of relevance include:

- communication: communicating by language, signs and symbols, carrying on conversations, and using communication devices and techniques

- mobility: walking, running or climbing, changing location or body position, carrying, moving or manipulating objects, and using various forms of transportation

- self-care: attending to one’s hygiene, dressing, eating and looking after one’s health

- domestic life: carrying out everyday tasks such as acquiring necessities (like a place to live and goods and services), preparing meals, caring for household objects and assisting others

- interpersonal interactions and relationships: relating with strangers, formal and informal social relationships, family and intimate relationships

- learning and applying knowledge: learning, applying the knowledge that is learned, thinking, solving problems, and making decisions

- community, social and civic life : engaging in community, civil and recreational activities

- general tasks and demands: carrying out single or multiple tasks, organising routines and handling stress

- major life areas: carrying out responsibilities at home, work or school and conducting economic transactions.

Finally, Contextual Factors including two domains:

- Environmental Factors: include a broad range of physical, social and attitudinal characteristics of the individual’s environment that may hinder or facilitate their capacity to be involved in their chosen activities.

- Personal Factors: include characteristics of the individual, other than impairments or functional capacity, which may exert an influence on the individual’s capacity to participate in activities. Included are factors such as age, gender, race, lifestyle, fitness, social and educational background, coping skills and life experience (Harries, 2008). Personal factors, although recognized as exerting an important influence on the functioning of the individual, are not classified within the ICF.

As previously mentioned, disability is considered to be the result of a complex relationship between the individual’s health condition and personal factors, as well as the external (environmental) factors that make up the situation in which the individual lives (Harries, 2008). Consequently, people with similar health conditions may have different experiences of disability due to the influence of personal or environmental factors (WHO, 2001). The WHO ICF provides a useful conceptual framework for guiding the development of needs assessment tools or for evaluating the comprehensiveness of existing tools (Harries, 2008). Support needs instruments that incorporate indicators or measures of personal factors would provide a useful source of information for qualifying the types and levels of supports that may be required (Lindeman, 2009). The implication is that rather than replicate all elements of the ICF framework, any assessment tool would incorporate the best mix of indicators or relevant domains of need. The preferred assessment tool(s) would still be consistent with the overarching ICF framework (Australian Productivity Commission (APC), 2011).

Maslow’s Hierarchy of Needs

As with the ICF, Maslow’s model considers a person’s state of functioning to be a dynamic interaction between external factors and the person’s capacity to function. Maslow’s model assumes higher level needs of the hierarchy only become relevant when needs at the lower level are fulfilled. A multitude of research (Harries, 2008) has discounted the hierarchical nature of this model, as people living in collectivist societies have been found to fulfil needs at the higher end of the hierarchy, while living in slums.

Although not useful as a hierarchy of need, Maslow’s model as a conceptualisation of various needs, is valuable. The model could provide a guiding schema for the development of a needs assessment tool, thereby ensuring comprehensive assessment of all physiological and safety needs, without neglecting the ultimate goal of ensuring the person reaches their maximum potential (Harries, 2008). Nosek and Fuhrer (1992) considered it an unfortunate reality for many individuals with very severe disabilities, living in institutional settings, that they have only had needs at lower levels of the hierarchy addressed (i.e., they are clothed, fed, housed, and are kept safe from illness or injury). Other aspects of their well-being have received little consideration, with few opportunities provided to enable higher order needs to be fulfilled. Whereas the application of resources directed towards needs at the lower physiological and safety levels of the hierarchy is very important for these individuals and all others (e.g., to assist with eating, drinking, medication management, and to maintain health status etc.), it is equally important to ensure that needs associated with higher levels of the hierarchy are addressed (e.g., social, esteem, and self- actualisation).

Alderfer’s (1969) Existence, Relatedness and Growth Theory is an extension of Maslow’s model whereby the domains of need are condensed into:

- Existence: Needs relating to health and safety

- Relatedness: Needs relating to love/belonging, inclusion, relationships and self esteem.

- Growth: Needs relating to self-actualisation: creativity and learning etc.

Bradshaw’s Needs Framework

Rather than specifying need domains along the lines of the Maslow model, this model of social need focuses on approaches for identifying and measuring needs. Bradshaw (1977) distinguished between four types of social need, two of which were external to the individual (normative and comparative need) and two of which related to the individual’s perceptions (felt and expressed needs).

Bradshaw’s framework involves four different ways of thinking about ‘need’.

Normative need is defined by reference to ‘appropriate’ standards or required levels of services or outcomes determined by expert opinion. Individuals or groups falling short of these standards are defined as being in need. Moreover, experts may have different and possibly conflicting standards.

Comparative need is determined by comparing the resources or services available in one area — be it a community, a population group or individual — with those that exist in another. A community, population group or person is considered to be in ‘need’ if they have say more health or social problems, or less access to services, than others. The main problem with the concept of comparative need are its two underlying assumptions — first, that similarities exist between the areas and second, that the appropriate response to the ‘problem’ is to align service levels. This need not hold true, for example, when both areas experience chronic shortages for a particular service.

Felt need has a subjective element and is defined in terms of what individuals state their needs to be or say they want. It can be defined easily by asking current or potential service users what they wish to have. However felt need by itself is generally considered to be an inadequate measure of ‘real need’. For example felt need can be inflated by users’ own high expectations.

Expressed need is defined in terms of the services people use. It is based on what can be inferred about a person or a community by observing their use of services (or waiting lists for services). A community or person who uses a lot of services is assumed to have high needs. While a community or person who does not, is assumed to have low needs. But expressed need is influenced by the availability of services — a person cannot use or put their name down on a waiting list for a service that is not offered.

Source: Bradshaw (1972).

This framework is relevant in disability policy. As Anglicare observed:

… the needs identified by Bradshaw, particularly perceived [felt] and normative needs resonate most closely with the types of need identified by Anglicare Australia network members. (sub. no 594, p. 6, as cited in Productivity Commission Report (APC, 2011)).

John O’Brien’s Five Valued Experiences - An Accomplishment Framework

John O’Brien was influential in the Normalisation and Social Role Valorisation movements as well as the move towards inclusive forms of service provision.

O’Brien discussed five closely linked service accomplishments that guide service staff in their work (O’Brien, 1989). Accomplishments describe worthy consequences of service activities. Each accomplishment supports a vital dimension of human experience that has been somewhat limited for people with disabilities. According to O’Brien (1989) The five valued experiences include:

- Growing in Relationships (Belonging)

- Contributing

- Sharing Ordinary Places

- Dignity of Valued Roles (Being respected)

- Making Choices

The five valued experiences are created by people’s own effort and the efforts of friends, family and community members, and are assisted by these accomplishments of human service providers:

- Community Presence: How can we increase the presence of a person in local community life?

- Community Participation: How can we expand and deepen people’s friendships?

- Promoting Choice: How can we help people have more control and choice in life?

- Supporting Contribution: How can we assist people to develop more competencies and contribute their unique gifts?

- Valued Roles: How can we enhance the reputation people have and increase the number of valued ways people can contribute? (O’Brien, 1989)

The Five Valued Experiences and Service Accomplishments can be used as a framework for developing a needs assessment. The Valued Experiences can identify areas of need, while the accomplishments can guide supports.

Measuring support needs

The development and use of support needs assessments have been driven by contemporary disability models in which the application of supports are considered necessary to enrich a person’s experience of disability. This conceptualisation of disability has challenged existing assessment approaches in which the focus has been on identifying deficits. The task now is to establish how to support and enable the individual with a disability to participate more fully in the activities and settings of their choice (Riches, 2008). An extension of this approach to identifying need for supports has involved attempts to match the allocation of support funding to previously identified needs.

There are currently no mandated assessment tools for assessing the supports needs of people receiving drop in support in Australia (ADHC, 2011). A small number of service providers do use standardised assessment tools such as the Supports Intensity Scale (SIS), Service Needs Assessment Profile (SNAP) and the Instrument for the Classification and Assessment of Need (I-CAN), while others use their own

in-house developed tools (ADHC, 2011). The advantage of assessment tools is that there is potential to measure the outcomes for clients over time. Service providers generally use assessment tools annually, and these tools can demonstrate changes over time (ADHC, 2011).

Ageing, Disability and Home Care (ADHC) suggest the identification and introduction of a standardised assessment approach for support services to be used as part of the person centred individual planning process. Review of the person centred plan on at least an annual basis, should trigger the reassessment of support needs (ADHC, 2011).

Support needs assessment instruments, to be most useful, should have the following features:

- be easily placed into practice and used by professionals, non- professionals, and stakeholders with a wide range of skills;

- produce consistent results and outcomes when used across service areas and regions;

- be person centred;

- provide accessible and understandable information to a wide range of stakeholders;

- identify the support needs of people with complex and challenging conditions;

- generate results that are applicable to decision making across a wide range of issues; and

- be designed to integrate in the support planning process the perspectives of individuals receiving support, their families and close friends, staff, and

Guscia, Eckberg, Harries and Kirby (2006) have suggested that one area not well assessed by instruments used within the disability sector is the impact of environmental factors on an individual’s need for support. They have recommended more comprehensive assessment of the environment utilising the World Health Organisation’s (WHO) International Classification of Functioning, Disability, and Health (ICF; WHO, 2001).

While the assessment process would primarily be about assessing an individual’s needs, it should not disregard their aspirations. The Productivity Commission (APC, 2011) sees merit in the approach employed in the United Kingdom whereby:

The purpose of a community care assessment is to identify and evaluate an individual’s presenting needs and how these impose barriers to that person’s independence and/or wellbeing. Once eligible needs are identified, councils should take steps to meet those needs in a way that supports the individual’s aspirations and the outcomes that they want to achieve. (UK Department of Health 2010, p. 20)

In addition to encompassing elements of self-care, communication and mobility, the assessment process should include aspects of learning and applying knowledge, and community and social participation. To do otherwise might mean the support needs of some individuals were systematically overlooked. Further to this, client- centred assessment necessarily requires the assessor to obtain ‘biographical

information‘ in order to arrive at an understanding of the client’s world view (Worth 1998). Without allowing the client to tell their own story, their account could become objectified and depersonalised through the assessment process so that their goals and values are hidden (Lindeman, 2009; Richards, 2000). While the individual undertaking assessments would be independent, it would be important to involve other interested parties in the assessment process. Ideally, these would be people who were familiar with the care and support needs of the individual, they might include family members, carers and direct support professionals.

The success of a needs based assessment system should be determined by the extent to which it leads to improvements in quality of life and opportunities for self- determination for the individual.

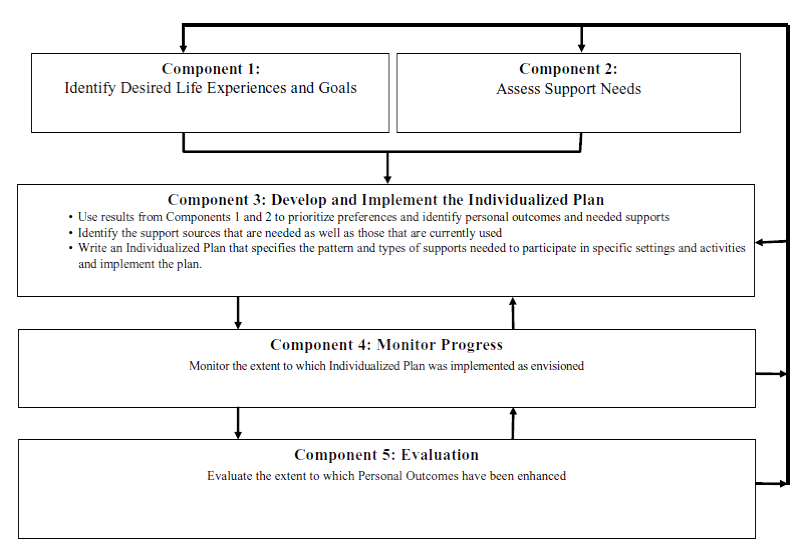

A Process Model of Needs Assessment

Thompson, Hughes and colleagues (2002) propose a four component approach for determining support needs and developing plans to meet these needs. The four components are as follows:

- Identify a person’s desired life experiences and goals,

- Determining an individual’s intensity of support needs across a wide range of environments and activities,

- Developing an individualized support plan, and

- Monitoring outcomes and assessing the effectiveness of the plan.

A process model of support needs, Buntinx & Schalock, 2010

The first component utilises a person centred planning process to identify any discrepancies between an individual’s current life experience and conditions, and his or her preferred or desired life experiences and conditions (Thompson & Hughes et al., 2002).

The second component entails a formal assessment process specifying the general characteristics of a person’s support needs. This is accomplished shortly after the visioning process identified in component one, and should reflect the frequency and duration of specific types of needed supports. A comprehensive assessment of the sources of support currently available to the person must be considered (Thompson & Hughes et al., 2002). Collectively, this information should provide an adequate and objective set of data from which to identify the intensity of individualised support needs and provide guidance for developing an individualised support plan.

The third component is the development of the individualised support plan, where the sources of support are identified based on a team process that considers resource and service availability or practicality.

The fourth component entails the follow-up and monitoring of an individual’s quality of life and the implementation of the plan. Finally an assessment and review of the plan is required.

Quantifying Support

When quantifying support needs for research or funding purposes it is important to collect information on the nature of the support that is required. Instruments assessing support needs use various methods to calculate the cost of support, or number of hours of support required per week.

The Supports Intensity Scale (SIS) measures support in terms of frequency (how often the support is needed), duration of support (when needed, how much time is required for the support), and type of support (what type of support is needed, for example supervision, full physical assistance). The SIS rates each of these dimensions on a Likert scale of 0 to 4.

The Service Need Assessment Profile (SNAP) measures each activity on a Likert scale of 1 to 5 where 1 = totally independent, or no support, and 5 = totally dependent on staff support. Computer software generates an individual profile that includes support hours required per day, which is then used to calculate staffing costs.

The Inventory for Client and Agency Planning (ICAP) rates maladaptive behaviours in terms of their frequency of occurrence and severity, from which a General Maladaptive Index (GMI) is derived (ranging on a scale from normal to severe).

The SIS stands out from the other assessment tool as it distinguishes between the frequency and duration of support required. In some instances a person may need support frequently but for a short duration each time, or considerable support only once a week (Swanton, 2010).

When measuring or assessing support needs, it is crucial to consider all dimensions of support including frequency, duration and type.

ADHC Banding Classifications

ADHC (2010). Drop-in Support Model - Standard. MDS Code 1.06

Drop-in support services are designed for clients with an intellectual or other disability with low to moderate levels of support need and higher levels of decision making capacity, who require up to 35 hours of direct support per week (ADHC, 2010). The main objective of the Drop-‐in support service model is to facilitate the development of independent living skills through the provision of support and assistance to a person or small group of people with disabilities; including the needs of Aboriginal and Culturally and Linguistically Diverse (CALD) populations utilising the service (ADHC, 2011).

The service will provide clients assistance with:

Personal care – completing or monitoring the completion of tasks such as:

- eating and drinking

- hygiene

- dressing and grooming

- bathing and toileting

Communication:

- developing communication skills

- developing interpersonal skills

Daily living care – completing or monitoring the completion of tasks such as:

- preparing meals and cooking

- clothes washing, drying and care

- shopping for food and household goods required for everyday life

- household cleaning, maintenance of hygienic and ordered living environment

Social skills and relationship:

- developing and maintaining contact with significant others (family, )

- developing and maintaining social contacts and friendships

- developing and maintaining good neighbour relations

Community access:

- travelling independently using public transport

- using community facilities e.g. library, swimming pool, banks

Leisure and recreation:

- participating in fitness, sport, recreational and leisure groups

- participating in adult education, employments skills and training

Day activities:

- accessing day activities, training, employment, volunteer and other day time activities, but not providing them

Health care:

- attending fitness, nutrition, sexual health and relationship programs

- attending to health and dental care as prescribed and documented by qualified medical and allied health practitioners

Managing behaviour:

- support the development of positive behaviours

- minimising behaviours that restrict participation in community activities or pose risk to self or others

- developing a contingency after hours plan for emergencies

Skills development:

- maximising personal independence through skills building

- minimising risk behaviours by learning citizenship and social norms

- building and encouraging employment related skills and activities Personal and financial accountability – skill building, mentoring and monitoring the completion of tasks such as:

- budgeting, managing finances and payment of bills

- handling money, and paying rent on time

The specific details of the services to be provided would be set out in the client’s individual support plan. This then informs the planning, organisation and coordination of services necessary to implement the plan. Each client within the service will receive a notional support package of hours according to a band. Any unused hours in the support package can be banked and may be drawn on by the client or others for specific purposes.

The intensity of support and care provided by the Drop-in Support Service Model ranges from:

Band 1 – Low (14 hours support per week)

Band 2 – Low to moderate (21 hours support per week)

Band 3 – Moderate to high (28 hours support per week)

Band 4 – High (35 hours support per week)

In a review prepared for ADHC of In Home Drop-In Accommodation Support, the O’Connell Advisory Group (2011) found that 92% of service providers surveyed reported that accessing the community is a major focus of the drop in support hours. Other important activities included:

- leisure and recreation (86%)

- providing skills development (85%)

- providing assistance with access to services (88%);

- undertaking a client risk assessment and developing plans (88%),

- maintaining and developing communication and social skills (86%)

The report also illustrated that the highest proportion of clients (approx 52%) are funded under the lowest support funding band, and so receive up to 14hours/week of direct support (ADHC, 2011). It was noted that there is a steep rise in the average number of hours of support needed per week when clients reach the age of 60 years, from 11.9 direct hours to 17.5 direct hours per week (47% increase) (ADHC, 2011).

Client support hours rise gradually between the ages of 45 and 60 years. These findings illustrate the need for an assessment tool to be flexible and allow for forward thinking, taking into account personal factors of an individual that may influence changing support needs.

Resource Allocation Systems

The resource allocation system (RAS) in the UK defines each person’s personal budget. The system must therefore give an indication of how much money should be made available to the person in their personal budget and say clearly what outcomes should be achieved through the use of that money.

Defining both the outcomes and resources early on in the process ensures that people can spend money in ways and at times that make sense to them.

By creating a personal budget, using a RAS, self-directed support offers the individual and their family both clarity of outcomes and flexible control of resources, while avoiding an over-reliance on pre-commissioned block-purchased services.

Having clarity of outcomes and resources also allows individuals and their families to develop personalised support plans appropriate to their own unique circumstances, aspirations and needs- rather than taking a one size fits all approach. As state resources are decided early on, the individual is free to draw on their own social and financial resources to implement support that looks beyond meeting basic needs and outside of the limited range of service solutions traditionally on offer.

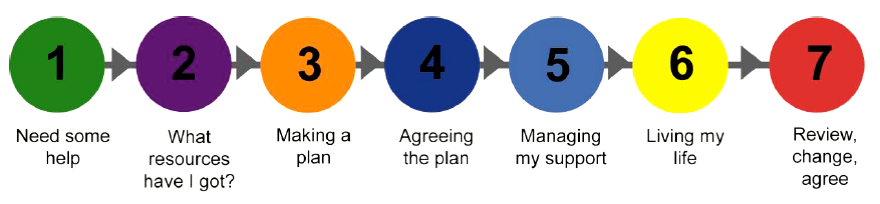

The seven steps of self-directed support

InControl UK 2012

This model of self directed support shows that a support needs assessment is completed at step 2. The RAS generates an indicative personal budget; this is one of the resources available to people in developing their plans.

Standardised Support Needs Assessment Tools

Assessment tools can be represented along a continuum of ‘highly formal’ to ‘highly informal’ (Lindeman, 2009). At the highly formal end of the continuum are the standardised tools that are norm referenced and which have been subjected to extensive field testing and statistical analysis. These standardised tools are said to rate highly in terms of reliability (they produce the same results regardless of who administers the tool) and validity (they measure what they are suppose to measure) (Lindeman, 2009). Arguments that support the use of formal, or structured, instruments include that they reduce the risk of inconsistency between assessors and enhance the service provider’s ability to collect reliable data.

Supports Intensity Scale (SIS)

The Supports Intensity Scale (SIS) (Thompson et al., 2004) was developed as part of a person centred support and assessment planning process by a team of people endorsed by the American Association of Mental Retardation (AAMR) – now the American Association on Intellectual and Developmental Disabilities (AAIDD). It was designed specifically to measure the level of practical supports required by persons with intellectual disabilities. Its development was informed from a quality of life framework (Thompson et al., 2009). The SIS has been tested rigorously and been found to have good psychometric properties. It is administered as a semi structured interview, by a qualified interviewer. The developers indicated that the SIS should be administered by a professional who has completed a four year degree program and is working in the field of human services (for example, a case manager, a psychologist, or a social worker). The assessment takes approximately one hour to complete.

The scale and subscales measure 57 life activities based on seven life activity areas: Home living activities, Community living activities, Lifelong learning activities, Employment activities, Health and Safety activities, Social activities and Protection and Advocacy. Each item for the seven areas is rated on a five point Likert scale from 0 to 4 in terms of frequency of support (less than monthly/monthly/weekly/ daily/hourly); daily support time (none/less than 30 minutes/30 minutes to less than 2 hours/2 hours to less than 4 hours/4 hours or more); and type of support (none/monitoring/verbal or gestural prompting/partial physical assistance/full physical assistance).

Additionally, the subscale measures Exceptional Medical Support Needed or Exceptional Behavioural Supports Needed. The first part of the subscale looks at Respiratory Care, Feeding Assistance and Lifting/transferring. Each item is rated on a three point Likert scale from 0 to 2 where 0 = No support needed, 1 = some support needed, and 2 = extensive support needed. The second part of the subscale looks as Externally Directed Destructiveness, Self Directed Destructiveness and Wandering off. Each item is rated on the same three point Likert scale from 0 to 2.

The Support Needs Scale provides a profile of needed supports in the seven life activity areas. Results are reported with an overall support needs score and percentile ranking of a person’s needs based on normed data.

The SIS has been found to be an effective instrument for measuring differences in support needs and informing decision making in regard to allocating funding (Wehmeyer et al., 2009). It was also found to be useful as a basis for person centred support planning, to contribute to a positive behavioural plan, and to document the level and type of support required to achieve personal goals. It is important to keep in mind that intellectual and related developmental disabilities are multifaceted conditions that result in a complex spectrum of intensity and type of support needs. One should not expect that the SIS, or any other singular supports assessment instrument will explain 100% of the variance in funding required to provide these supports (Wehmeyer et al., 2009).

Instrument for the Classification and Assessment of Need (I-CAN)

The I-CAN was designed to assess frequency and intensity of support needs for daily living. Developed from the conceptual framework of the WHO International Classification of Functioning, Disability and Health 2001. The I-CAN has two subscales – Health and Well Being (HWB) and Activities and Participation (A&P).

The first subscale, Health and Well Being looks at a person’s physical health, mental/emotional health, behaviour and health services. The second, Activities and Participation, includes knowledge and general tasks, communication, mobility, self care, domestic life, interpersonal interactions, relationships, community, social and civic life.

The scale has been used with people with a diverse range of disabilities in respite and residential settings. A short version of the I-CAN has recently been developed. I- CAN has been shown to have inter-rater reliability ranging from 0.96 to 1.0, though this may be attributed to the group interview assessment process itself. Test-retest reliability ranged from -0.22 to 0.51 (measured at 1 and 2 years). Those involved with the tools development note: ‘Although these generally low and non significant results could indicate poor reliability, alternatively they may indicate sensitivity to real change’ (Arnold et al, 2008).

Service Needs Assessment Profile (SNAP)

Developed in Australia, the SNAP was designed specifically to estimate support needs and associated costs for people receiving disability support services. It generates an individual support profile that includes an allocated time, in hours per day, for providing support to the individual, and a night support rating (APC, 2011).

Assessments contain a series of statements to describe the support needs of individuals in relation to various aspects of daily living. The statements provide a description of the levels of support required, ranging from independence to full support. The scale measures 29 areas of functioning within 5 domains:

- personal care bathing, dressing, eating, meal preparation, household tasks, and self-protective skills

- physical health ambulation, health issues, incontinence, mobility, pressure care and epilepsy

- behaviour support type of behaviour, support requirements, behavioural risk, behavioural programs, and mental health issues

- night support safe practices, sleeping patterns, physical support needs, health and monitoring, and behavioural issues

- social support communication, social, leisure and money skills, day support requirements, skill development options and travel needs (APC, 2011).

SNAP has been designed to allow primary carers to complete the assessment in the service setting. No specific detail is given in the SNAP manual with respect to training or who is best qualified to provide ratings other than the ‘person completing the assessment must have a good knowledge of the individual being assessed’. The scale takes around 20 minutes to complete (APC, 2011).

SNAP has been used in New South Wales to guide the funding of accommodation and day support services and has been trialled by the South Australian Department for Families and Communities (APC, 2011).

Disability Support Training and Resource Tool (D-START)

The Disability Support Training and Resource Tool (D-START) was designed to assess the needs, capabilities and aspirations of adults with different types of disabilities. In addition to identifying current support needs, D-START is intended to highlight possible changing needs. D-START can be used for generating estimates of support needs for individual planning and resource allocation purposes.

The underlying structure of D-START is compatible with the ICF framework to ensure comprehensive coverage of life domains, which include:

- Medical and health supports

- Supports for activities of daily living

- Daily tasks such as dressing, eating, bathing

- Community and household tasks

- Recreation and leisure activities

- Functional skills: communication, social/emotional skills

- Behaviour supports

- Personal risk factors such as household and community safety, cultural background, life stage transitions

- Environmental factors such as technology, natural and paid supports and relationships, services

The standard form takes around 45-90 minutes to complete. The developers indicated that assessors should be trained to maximise accuracy. Test-retest reliabilities for subscales and total score range from 0.80 to 0.98, while inter-rater reliabilities for subscales and total score range from 0.56 to 0.98 (APC, 2011).

Inventory for Client and Agency Planning (ICAP) and adaptive behaviour scales

Adaptive behaviour scales measure a person’s competency at completing an activity, while support need assessments measure the level of support someone would require to complete an activity etc.

The Inventory for Client and Agency Planning (ICAP) assesses adaptive and maladaptive behaviours. ICAP provides information on an individual’s ability to function in the areas of motor, personal living, community living, and social and communication skills. Information is provided on an individual’s maladaptive behaviour in a further eight areas — hurtful to self; hurtful to others; destructive to property; disruptive behaviour; unusual or repetitive habits; socially offensive behaviour; inattentive behaviour; and uncooperative behaviour (APC, 2011).

Each item represents a statement of ability and is given a rating and associated score (does very well, does fairly well, does but not well, and never or rarely).

Maladaptive behaviours are rated in terms of their frequency of occurrence and severity. Measures of adaptive and maladaptive behaviour are combined in a service score. ICAP also covers a number of other areas, including demographic information, diagnostic and functional status, residential placement, social and leisure activities, and daytime programs and support services (APC, 2011).

According to the manual, the tool has good psychometric properties with both test- retest and inter-rater reliability for the service score of more than 0.80 to 0.90 (Harries 2005).

ICAP can be completed in approximately 20 minutes by a parent, teacher or care person who is well acquainted with the person being assessed. No specific training is recommended for its implementation other than self-study of the ICAP manual (APC, 2011).

Other adaptive behaviour instruments include the Scales of Independent Behaviour (SIB-R). The Vineland Adaptive Behaviour Scale and the AAMR Adaptive Behaviour Scales.

Queensland Ongoing Needs Identification (ONI)

The Ongoing Needs Identification (ONI) tool is designed to prompt timely and appropriate service delivery, referral and/or further assessment based on the issues and needs that are identified for each service user. In Queensland, the ONI is the preferred tool for the initial assessment and referral of eligible clients.

This tool can be used in either a telephone or face-to-face interview.

There are eight profiles in the ONI, not all of which are mandatory.

| ONI Profile | Description | Use |

|

1. Functional profile (FP) |

Functional assessment tool that identifies equipment and/or aids the service user may use, and triggers comprehensive/ specialist assessment if required. |

Mandatory |

| 2. HACC MDS Supplementary items (HS) | Identifies HACC MDS items if the living arrangements profile and carers profile not completed. | Mandatory if the living arrangements profile and/or carer profile are not completed. |

| 3. Living arrangements profile (LAP) | Identifies service user’s living arrangements, legal and financial management status. | Mandatory if the HACC MDS Supplementary Items form not Completed |

|

4. Carer profile (CP) |

Identifies carer arrangements, carer issues and the sustainability of carer arrangements. | Mandatory where a carer exists and if the HACC MDS Supplementary Items form is not completed. |

| 5. Health conditions profile (HCP) | Identifies issues about the service user’s health and physical wellbeing and will trigger appropriate referral. | Optional depending on identified service user issues. |

|

6. Psychosocial profile (PP) |

Identifies issues about the service user’s social, emotional and mental health and will trigger appropriate referral. | Optional depending on identified service user issues. |

| 7. Health behaviours profile (HBP) | Identifies service user’s lifestyle behaviours and will trigger issues and appropriate referral. | Optional depending on identified service user issues. |

| 8. ONI priority rating (OPR) | Includes options for establishing a service user priority rating based on the information collected in the ONI. | Optional depending on identified service user issues and service provider policies. |

The tool should not be used as a structured interview, rather as a guide to a conversation with a service user. Responses for activities in the Functional Profile are scored from 0 to 2 in terms of level of support required where 0 = completely unable, 1 = able, with some help and 2 = without help.

The ONI was designed to be used as a screening tool, and not a resource allocation tool as is the purpose of the other abovementioned needs assessment tools.

InControl UK - Self Assessment Questionnaire (SAQ)

The SAQ is a standardised assessment carried out by individuals to identify their own needs and eligibility for support. The questionnaire is part of the Resource Allocation System and helps determine, through a points system, how much money an individual is entitled to (InControl UK, 2011).

The self-report questionnaire initially asks about quality of life, followed by questions around support in eight domains: complex needs and risks, meeting personal needs, meals and nutrition, work, learning and leisure, making important decisions about life, being part of the local community, essential family/caring role, available social support/relationships. There is one part for an unpaid/natural support person to complete, if relevant.

Each domain has a number of questions, and also space for additional comments. The areas of need of the eight domains, follow a hierarchy of need.

Each question in the self assessment form has a number of points attached to it. The total number of points is added and correlates with an amount of money. This is an indicative amount, to consider while developing a person centred support plan. The actual amount of money someone receives at the end of the process may be different.

Non Standardised Support Needs Assessment Tools

As previously mentioned, assessment tools may fit into a continuum of highly formal to highly informal. Non standardised tools generally have not been rigorously tested for validity and reliability. They may simply be lists of domains or headings such as ’mobility’ with free text space for the assessor to record any information they consider to be relevant (Lindeman, 2009). Woods and Baldwin (1998) note that while needs assessment processes that include predetermined lists are helpful to ensure that an adequate range of activities is considered for assessment, it cannot substitute for more open-ended techniques that are based upon the assessor using good professional judgement. They also note that while all clients share universal needs, most clients will also have specific needs, often relating to religious, ethnic and other cultural factors including specific aspects of their disabilities (Woods & Baldwin 1998).

The implication is that formal/structured (standardised tools) are less likely to capture client diversity than less structured, open-ended, and fluid processes.

Recommendations for Tool Development

In light of the literature, clear recommendations for developing a support needs assessment tool are as follows:

- The tool is used as one component of a process model of a person centred support needs

- The development of the model of needs assessment is guided by John O’Brien’s five valued experiences.

- The assessment tool itself is built on the principles of the World Health Organisation’s International Classification of Functioning, Health and Disability Framework

- The tool has two parts:

- Standard Assessment (built on the WHO ICF)

- Personalised Assessment (based on visioning conversation)

- The amount of support required for identified needs is measured in terms of:

- Frequency of support (hourly, daily, weekly, monthly, none)

- Duration of support, when required (response in minutes e.g., 5mins, 45 mins, 120mins)

- Type of support (Full physical assistance, active support – prompts, supervision, none )

- The Frequency and Duration of support will be calculated to determine the number of hours of support required per week. The number of hours will correspond to a Band identified by FACS.

- As the tool will be used in a model of person centred support needs assessment, it will be flexible and personalised to each individual, and the model will involve visioning and planning to determine the best use of the hours allocated.

References

ADHC (2010). Drop-in Support Model – -Standard. MDS Code 1.06

ADHC (2011). Review of In Home Drop-In and Accommodation Support. Final Report. Department of Family and Community Services. Ageing, Disability and Home Care. Prepared by O’Connell Advisory Group.

Australian Productivity Commission (APC) (2011), Disability Care and Support, Report no. 54, Canberra

Alderfer, C. P. (1969) An empirical test of a new theory of human need.

Organisational behaviour and human performance, 4(2) 142-175

Arnold, S. R. C., Riches, V. C., Parmenter, T. R., Llewellyn, G., Chan, J. & Hindmarsh, G. (2008). I-CAN: Instrument for the Classification and Assessment of Support Needs, Instruction Manual V4.2. Sydney, Australia: Centre for Disability Studies, Faculty of Medicine, University of Sydney.

Bradshaw, J. (1977). The concept of social need. In N. Gilbert & H. Specht (Eds.),

Planning for social welfare: Issues, models and tasks. (pp 290-296). Engelwood Cliffs. New Jersey: Prentice Hall.

Bruininks, R., Hill, B., Weatherman, R. & Woodcock, R. (1986). ICAP Inventory for Client and Agency Planning Examiners Manual. Chicago: Riversdale.

Guscia, R., Ekberg, S., Harries, J. & Kirby, N. (2006). Measurement of environmental constructs in disability assessment instruments. Journal of Policy and Practice in Intellectual Disabilities, 3, 173-180.

Guscia, R., Harries, J., Kirby, N. & Nettlebeck, T. (2006). Rater bias and the measurement of support needs. Journal of Intellectual and Developmental Disability, 31(3): 156-160.

Guscia, R., Harries, J., Kirby, N., Nettlebeck, T. & Taplin, J. (2005). Reliability of the Service Need Assessment Profile (SNAP): A measure of support for people with disabilities. Journal of Intellectual and Developmental Disability, 30(1) 24- 30.

Harries, J. (2008). Support Needs Assessment for Individuals with Intellectual Disabilities: An investigation of the Nature of the Support Needs Construct and Disability Factors that Impact on Support Needs. PhD Thesis. University of Adelaide.

Howard Research and Management Consulting (2007). Needs Based Assessment Tools: Environmental Scan and Literature Review. Persons with Developmental Disabilities, Calgary Region Community Board.

In Control UK (2012). Building a new relationship with children, young people and families. September, 2012, West Midlands, UK.

Kirby, N., Nettlebeck, T., Taplin, J., Guscia, R., Harries, J., Partridge, K., Thomson, S. & Wyatt, K. (2004). Evaluating the Service Needs Assessment Profile (SNAP). Paper presented at the National Accommodation and Community Support Conference, March 2004, Melbourne, Victoria.

Lindeman, M. (2009). Emerging tensions in the use of assessment tools in home and community care. Practice Reflexions, 4(1) 41-52.

Luckasson, R., Borthwick-Duffy, S., Buntinx, W. H. E., Coulter, D. L., Craig, E. M., Reeve, A., Schalock, R. L., Snell, M. A., Spitalnik, D. M., Spreat, S. & Tasse,

- J. (2002). Mental retardation: Definition, classification and system of supports. Washington, DC: American Association on Mental Retardation.

Maslow, A. (1970). Motivation and Personality. New York: Harper and Row.

Nosek, M. A. & Fuhrer, M. J,. (1992). Independence among people with disabilities: A heuristic model. Rehabilitation Counselling Bulletin, 36, 6-20.

O’Brien, J. (1989). What’s worth working for? Leadership for better quality human services. Georgia: Responsive System Associates.

Richards, S. (2000), ‘Bridging the divide: elders and the assessment process’, British Journal of Social Work, 30, 1: 37-49.

Riches, V. C., Parmenter, T. R., Llewellyn, G., Hindmarsh, G. & Chan, J. (2008). I- CAN: A New Instrument to Classify Support Needs for People with Disability: Part 1. Journal of Applied Research in Intellectual Disabilities 22, 326-339.

Swanton, S. (2010). A tool to determine support needs for community life. Learning Disability Practice, 13(8), 24-28.

Tasse, M. J. (2004). Support Intensity Scale: A Tool to Help in Person Centred Supports Planning. AAMR Reinventing Quality Conference, Philadelphia, PA, August 10.

Thompson, J. R., Bradley, V. J., Buntinx, W. H. E., Schalock, R. L., Shogren, K. A., Snell, M. E. & Wehmeyer, M. L. et al., (2009). Conceptualising Supports and the Support Needs of People with Intellectual Disability. Journal of Intellectual and Developmental Disabilities 47(2) 135-146.

Thompson, J. R., Bryant, B., Campbell, E. M., Hughes, C., Rotholz, D. A., Schalock,

- L., Silverman, W., Tasse, M. J. & Wehmeyer, M. (2004). Supports Intensity Scale: Users manual. Washington, DC: American Association on Mental Retardation.

Thompson, J. R., McGrew, K. S. & Bruininks, R. H. (2002). Pieces of the Puzzle: Measuring the Personal Competence and Support Needs of Persons Intellectual Disabilities. Peabody Journal of Education, 77(2) 23-39.

Wehmeyer, M., Chapman, T. E., Little, T. D., Thompson, J. R., Schalock, R. & Tasse,

- J. (2009). Efficacy of the Supports Intensity Scale (SIS) to Predict Extraordinary Support Needs. American Journal of Intellectual and Developmental Disability. 114 (1): 3-14.

Woods, P.A. and Baldwin, S. (1998), ‘Assessment of need and case management: an evolving concept’, in Baldwin, S. (ed.), Needs assessment and community care: clinical practice and policy making, Oxford, Butterworth-Heinemann.

World Health Organisation WHO. (2001). International Classification of Functioning, Disability and Health (ICF). Geneva: Author.

Worth, A. (1998), ‘Community care assessment of older people: identifying the contribution of community nurses and social workers’, Health and Social Care in the Community, 6, 5: 382-386.